Early signs of plant community responses to climate warming along mountain roads in Switzerland

Evelin Iseli, Nathan Diaz Zeugin, Camille Brioschi, Jake Alexander, Jonathan Lenoir

This article is a preprint, posted July 16, 2024.

Abstract

-

Global warming is pushing species to shift their ranges towards higher latitudes and elevations, causing a reassembly of plant communities potentially accompanied by community thermophilization (i.e., an increasing number or cover of thermophilic species, sometimes at the expense of mesic or cold-adapted species). Given the large variation typically observed in the magnitude and direction of range shifts, quantifying community thermophilization might provide a sensitive method to detect range shifts within short time periods and across limited spatial extents. Assessing changes in plant community composition as a whole might integrate early signs of range shifts across co-occurring species while accounting for changes in both occurrence and abundance.

-

Here, we combine an assessment of (i) species-level range shifts, (ii) changes in species richness and (iii) changes in community-inferred temperatures along three mountain roads in Switzerland to ask whether plant communities have responded to warming climate over a 10 year period, and whether community thermophilization is an appropriate metric for early detection of these changes.

-

We found a community thermophilization signal of +0.13°C over the 10-year study period based on presence-absence data only. Despite significant upward shifts of species’ upper range limits in the lower part of the studied elevational gradient and a decrease in species richness at high elevations, significant thermophilization was not detectable if community- inferred temperatures were weighted by species’ covers. Low cover values of species that were gained or lost over the study period and their similar species-specific temperatures to resident species explained the discrepancy between the thermophilization detected in either cover-weighted or unweighted models.

-

Synthesis. Our work shows that plant species are shifting to higher elevations along roadsides in the western Swiss Alps and that this translates into a detectable warming signal of plant communities within 10 years. However, the species-level range shifts and the community-level warming effect are mostly based on low cover values of gained/lost species, preventing the detection of community thermophilization signals when incorporating cover changes. We therefore recommend using unweighted approaches for early detection of community-level responses to changing climate, ideally set into context by also assessing species-level range shifts.

Deep learning to extract the meteorological by-catch of wildlife cameras

Jamie Alison, Stephanie Payne, Jake M. Alexander, Anne D. Bjorkman, Vincent Ralph Clark, Onalenna Gwate, Maria Huntsaar, Evelin Iseli, Jonathan Lenoir, Hjalte Mads Rosenstand Mann, Sandy-Lynn Steenhuisen, Toke Thomas Høye

Published: 09 December 2023, View article

Abstract

Microclimate—proximal climatic variation at scales of metres and minutes—can exacerbate or mitigate the impacts of climate change on biodiversity. However, most microclimate studies are temperature centric, and do not consider meteorological factors such as sunshine, hail and snow. Meanwhile, remote cameras have become a primary tool to monitor wild plants and animals, even at micro-scales, and deep learning tools rapidly convert images into ecological data. However, deep learning applications for wildlife imagery have focused exclusively on living subjects. Here, we identify an overlooked opportunity to extract latent, ecologically relevant meteorological information. We produce an annotated image dataset of micrometeorological conditions across 49 wildlife cameras in South Africa’s Maloti-Drakensberg and the Swiss Alps. We train ensemble deep learning models to classify conditions as overcast, sunshine, hail or snow. We achieve 91.7% accuracy on test cameras not seen during training. Furthermore, we show how effective accuracy is raised to 96% by disregarding 14.1% of classifications where ensemble member models did not reach a consensus. For two-class weather classification (overcast vs. sunshine) in a novel location in Svalbard, Norway, we achieve 79.3% accuracy (93.9% consensus accuracy), outperforming a benchmark model from the computer vision literature (75.5% accuracy). Our model rapidly classifies sunshine, snow and hail in almost 2 million unlabelled images. Resulting micrometeorological data illustrated common seasonal patterns of summer hailstorms and autumn snowfalls across mountains in the northern and southern hemispheres. However, daily patterns of sunshine and shade diverged between sites, impacting daily temperature cycles. Crucially, we leverage micrometeorological data to demonstrate that (1) experimental warming using open-top chambers shortens early snow events in autumn, and (2) image-derived sunshine marginally outperforms sensor-derived temperature when predicting bumblebee foraging. These methods generate novel micrometeorological variables in synchrony with biological recordings, enabling new insights from an increasingly global network of wildlife cameras.

Examples of the four classes of micrometeorological conditions in two representative high-elevation plots in Switzerland (CH) and South Africa (ZA). From: Global Change Biology | Environmental Change Journal | Wiley Online Library

Positive and negative plant−plant interactions influence seedling establishment at both high and low elevations

Chantal M. Hischier, Janneke Hille Ris Lambers, Evelin Iseli & Jake M. Alexander

Published: 24 November 2023, View article

Abstract

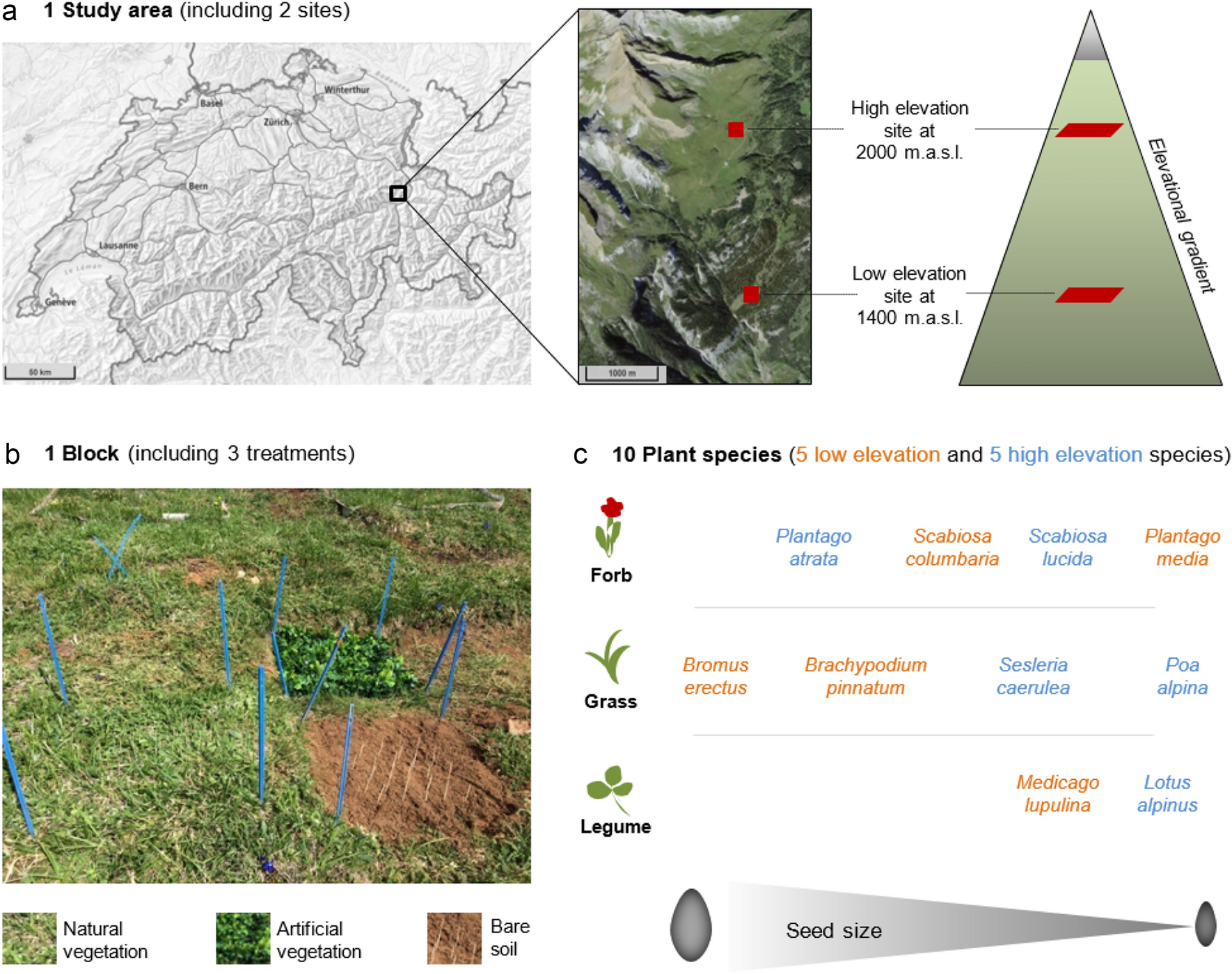

Deciphering how plants interact with each other across environmental gradients is important to understand plant community assembly, as well as potential future plant responses to environmental change. Plant−plant interactions are expected to shift from predominantly negative (i.e. competition) to predominantly positive (i.e. facilitation) along gradients of environmental severity. However, most experiments examine the net effects of interactions by growing plants in either the presence or absence of neighbours, thereby neglecting the interplay of both negative and positive effects acting simultaneously within communities. To partially unravel these effects, we tested how the seedling establishment of 10 mountain grassland plants varied in the presence versus absence of plant communities at two sites along an elevation gradient. We created a third experimental treatment (using plastic plant mats to mimic surrounding vegetation) that retained the main hypothesised benefits of plant neighbours (microsite amelioration), while reducing a key negative effect (competition for soil resources). In contrast to our expectations, we found evidence for net positive effects of vegetation at the low elevation site, and net negative effects at the high elevation site. Interestingly, the negative effects of plant neighbours at high elevation were driven by high establishment rates of low elevation grasses in bare soil plots. At both sites, establishment rates were highest in artificial vegetation (after excluding two low elevation grasses at the high elevation site), indicating that positive effects of above-ground vegetation are partially offset by their negative effects. Our results demonstrate that both competition and facilitation act jointly to affect community structure across environmental gradients, while emphasising that competition can be strong also at higher elevations in temperate mountain regions. Consequently, plant−plant interactions are likely to influence the establishment of new, and persistence of resident, species in mountain plant communities as environments change.

Experimental design and selected focal plant species. From: Positive and negative plant−plant interactions influence seedling establishment at both high and low elevations

Rapid upwards spread of non-native plants in mountains across continents

Evelin Iseli, Chelsea Chisholm, Jonathan Lenoir, Sylvia Haider, Tim Seipel, Agustina Barros, Anna L. Hargreaves, Paul Kardol, Jonas J. Lembrechts, Keith McDougall, Irfan Rashid, Sabine B. Rumpf, José Ramón Arévalo, Lohengrin Cavieres, Curtis Daehler, Pervaiz A. Dar, Bryan Endress, Gabi Jakobs, Alejandra Jiménez, Christoph Küffer, Maritza Mihoc, Ann Milbau, John W. Morgan, Bridgett J. Naylor, Aníbal Pauchard, Amanda Ratier Backes, Zafar A. Reshi, Lisa J. Rew, Damiano Righetti, James M. Shannon, Graciela Valencia, Neville Walsh, Genevieve T. Wright & Jake M. Alexander

Published: 26 January 2023, View article

Abstract

High-elevation ecosystems are among the few ecosystems worldwide that are not yet heavily invaded by non-native plants. This is expected to change as species expand their range limits upwards to fill their climatic niches and respond to ongoing anthropogenic disturbances. Yet, whether and how quickly these changes are happening has only been assessed in a few isolated cases. Starting in 2007, we conducted repeated surveys of non-native plant distributions along mountain roads in 11 regions from 5 continents. We show that over a 5- to 10-year period, the number of non-native species increased on average by approximately 16% per decade across regions. The direction and magnitude of upper range limit shifts depended on elevation across all regions. Supported by a null-model approach accounting for range changes expected by chance alone, we found greater than expected upward shifts at lower/mid elevations in at least seven regions. After accounting for elevation dependence, significant average upward shifts were detected in a further three regions (revealing evidence for upward shifts in 10 of 11 regions). Together, our results show that mountain environments are becoming increasingly exposed to biological invasions, emphasizing the need to monitor and prevent potential biosecurity issues emerging in high-elevation ecosystems.

Moths complement bumblebee pollination of red clover: a case for day-and-night insect surveillance

Abstract

Recent decades have seen a surge in awareness about insect pollinator declines. Social bees receive the most attention, but most flower-visiting species are lesser known, non-bee insects. Nocturnal flower visitors, e.g. moths, are especially difficult to observe and largely ignored in pollination studies. Clearly, achieving balanced monitoring of all pollinator taxa represents a major scientific challenge. Here, we use time-lapse cameras for season-wide, day-and-night pollinator surveillance of Trifolium pratense (L.; red clover) in an alpine grassland. We reveal the first evidence to suggest that moths, mainly Noctua pronuba (L.; large yellow underwing), pollinate this important wildflower and forage crop, providing 34% of visits (bumblebees: 61%). This is a remarkable finding; moths have received no recognition throughout a century of T. pratense pollinator research. We conclude that despite a non-negligible frequency and duration of nocturnal flower visits, nocturnal pollinators of T. pratense have been systematically overlooked. We further show how the relationship between visitation and seed set may only become clear after accounting for moth visits. As such, population trends in moths, as well as bees, could profoundly affect T. pratense seed yield. Ultimately, camera surveillance gives fair representation to non-bee pollinators and lays a foundation for automated monitoring of species interactions in future.